4. PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES

最后更新于:2022-04-01 04:42:53

## 4.1\. WHAT’S THE BIG PICTURE?[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#what-s-the-big-picture "Permalink to this headline")

Programming, sometimes referred to as coding, is a nuts and bolts activity for computer science. While this book won’t teach you how to program (we’ve given some links to sites that can do this in the introduction), we are going to look at what a programming language is, and how computer scientists breath life into a language. From a programmer’s point of view, they type some instructions, and the computer follows them. But how does the computer know what to do? Bear in mind that you might be using one of the many languages such as Python, Java, Scratch, Basic or C#, yet computers only have the hardware to follow instructions in one particular language, which is usually a very simple “machine code” that is hard for humans to read and write. And if you invent a new programming language, how do you tell the computer how to use it?

In this chapter we’ll look at what happens when you write and run a program, and how this affects the way that you distribute the program for others to use.

We start with an optional subsection on what programming is, for those who have never programmed before and want an idea about what a program is. Examples of very simple programs in Python are provided, and these can be run and modified slightly. Working through this section should give you sufficient knowledge for the rest of this chapter to make sense; we won’t teach you how to program, but you will get to go through the process that programmers use to get a program to run. Feel free to skip this section if you are already know a bit about programming.

A subsection on what this chapter focuses on then follows. Everybody should read that section.

### 4.1.1\. WHAT IS PROGRAMMING?[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#what-is-programming "Permalink to this headline")

Note: This section is intended for those who are unfamiliar with programming. If you already know a little about programming, feel free to skip over this section. Otherwise, it will give you a quick overview so that the remainder of the chapter makes sense.

An example of the simplest kind of program is as follows — it has five instructions (one on each line) that are followed one after the other.

~~~

print("************************************************")

print("************************************************")

print("*** Welcome to computer programming, Student ***")

print("************************************************")

print("************************************************")

~~~

This program is written in a language called Python, and when the program runs, it will print the following text to the screen

~~~

************************************************

************************************************

*** Welcome to computer programming, Student ***

************************************************

************************************************

~~~

In order to run a Python program, we need something called a Python interpreter. A Python interpreter is able to read your program, and process it. Below is a Python interpreter that you can use to run your own programs. If you have a Python interpreter installed on your computer (ask your teacher if you are following this book for a class and are confused) and know how to start it and run programs in it, you can use that.

Run

Output:

Try changing the program so that it says your name instead of *Student*. When you think you have it right, try running the program again to see. Make sure you don’t remove the double quotes or the parentheses (round brackets) in the program by mistake. What happens if you spelt “programming” wrong? Does the computer correct it? If you are completely stuck, ask your teacher for help before going any further.

Hopefully you figured out how to make the program print your name. You can also change the asterisks (*) to other symbols. What happens if you do remove one of the double quotes or one of the parentheses? Try it!

If you change a critical symbol in the program you will probably find that the Python interpreter gives an error message. In the online Python interpreter linked to above, it says “ParseError: bad input on line 1”, although different interpreters will express the error in different ways. If you have trouble fixing the error again, just copy the program back into Python from above.

Programming languages can do much more than print out text though. The following program is able to print out multiples of a number. Try running the program.

~~~

print("I am going to print the first 5 multiples of 3")

for i in range(5):

print(i*3)

~~~

The first line is a print statement, like those you saw earlier, which just tells the system to put the message on the screen. The second line is a *loop*, which says to repeat the lines after it 5 times. Each time it loops, the value of i changes. i.e. the first time i is 0, then 1, then 2, then 3, and finally 4\. It may seem weird that it goes from 0 to 4 rather than 1 to 5, but programmers tend to like counting from 0 as it makes some things work out a bit simpler. The third line says to print the current value of i multiplied by 3 (because we want multiples of 3). Note that there is *not* double quotes around the last print statement, as they are only used when we want to print out a something literally as text. If we did put them in, this program would print the text “i*3” out 5 times instead of the value we want!

Try make the following changes to the program.

* Make it print multiples of 5 instead of 3\. Hint: You need to change more than just the first line — you will need to make a change on the third line as well.

* Make it print the first 10 multiples instead of the first 5\. Make sure it printed 10 multiples, and not 9 or 11!

You can also loop over a list of data. Try running the program below. It will generate a series of “spam” messages, one addressed to each person in the recipients list!

Note that the # symbol tells the computer that it should ignore the line, as it is a comment for the programmer.

~~~

#List of recipients to generate messages for

spam_recipients = ["Heidi", "Tim", "Pondy", "Jack", "Caitlin", "Sam", "David"]

#Go through each recipient

for recipient in spam_recipients:

#Write out the letter for the current recipient

print("Dear " + recipient + ", \n")

print("You have been successful in the random draw for all people ")

print("who have walked over a specific piece of ground located 2 meters ")

print("from the engineering road entrance to Canterbury University.\n")

print("For being successful in this draw you, " + recipient + ", win ")

print("a prize of 10 million kilograms of chocolate!!!\n")

print("And " + recipient + " if you phone us within the next 10 minutes ")

print("you will get a bonus 5 million kilograms of chocolate!!! \n")

print("\n\n\n") #Put some new lines between the messages

~~~

Try changing the recipients or the letter. Look carefully at all the symbols that were used to include the recipient’s name in the letter.

**Jargon Buster**

The detailed requirements of a programming language about exactly which characters need to be used and where, is called its *syntax*. In the example above, the syntax for the list of names requires square brackets around the list, inverted commas around the names, and a comma between each one. If you make a mistake, such as leaving out one of the square brackets, the system will have a *syntax error*, and won’t be able to run the program. Every symbol counts, and one small error in a program can stop it running, or make it do the wrong thing.

Programs can also use *variables* to store the results of calculations in, receive user input, and make decisions (called *conditionals*, such as *if* statements). Try running this program. Enter a number of miles to convert when asked. Don’t put units on the number you enter; for example just put “12”.

~~~

print("This program will convert miles to kilometers")

number_of_miles = int(input("Number of miles: "))

if number_of_miles < 0:

print("Error: Can only convert a positive number of miles!")

else:

number_of_kilometers = number_of_miles / 0.6214

print("Calculated number of kilometers...")

print(number_of_kilometers)

~~~

The first line is a *print* statement (which you should be very familiar with by now!) The second line asks the user for a number of miles which is converted from input text (called a string) to an integer, the third line uses an *if* statement to check if the number entered was less than 0, so that it can print an error if it is. Otherwise if the number was ok, the program jumps into the *else* section (the error is not printed because the *if* was not true), calculates the number of kilometers (there are 0.6214 kilometers in a mile), stores it into a *variable* called number_of_kilometers for later reference, and then the last line prints it out. Again, we don’t have quotes around number_of_kilometers in the last line as we want to print the value out that is stored in the number_of_kilometers variable. If this doesn’t make sense, don’t worry. You aren’t expected to know how to program for this chapter, this introduction is only intended for you to have some idea of what a program is and the things it can do.

If you are keen, you could modify this program to calculate something else, such as pounds to kilograms or farenheit to celcius. It may be best to use an installed Python interpreter on your computer rather than the web version, as the web version can give very unhelpful error messages when your program has a mistake in it (although all interpreters give terrible error messages at least sometimes!)

Programs can do many more things, such as having a graphical user interface (like most computer programs you will be familiar with), being able to print graphics onto a screen, or being able to write to and from files on the computer in order to save information between each time you run the program.

### 4.1.2\. WHERE ARE WE GOING?[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#where-are-we-going "Permalink to this headline")

When you ran the programs, it might have seemed quite magical that the computer was able to instantly give you the output. Behind the scenes however, the computer was running your example programs through another program in order to convert them into a form that it could make sense of and then run.

Firstly, you might be wondering why we need languages such as Python, and why we can’t give computers instructions in English. If we typed into the computer “Okay computer, print me the first 5 multiples of 3”, there’s no reason that it would be able to understand. For starters, it would not know what a “multiple” is. And it would not even know how to go about this task. Computers cannot be told what every word means, and they cannot know how to accomplish every possible task. Understanding human language is a very difficult task for a computer, as you will find out in the Artificial Intelligence chapter. Unlike humans who have an understanding of the world, and see meaning, computers are only able to follow the precise instructions you give them. Therefore, we need languages that are constrained and unambiguous that the computer “understands” instructions in. These can be used to give the computer instructions, like those in the previous section.

It isn’t this simple though, a computer cannot run instructions given directly in these languages. At the lowest level, a computer has to use physical hardware to run the instructions. Arithmetic such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, or simple comparisons such as less than, greater than, or equal to are done on numbers represented in binary by putting electricity through physical computer chips containing transistors. The output is also a number represented in binary. Building a fast and cheap circuit to do simple arithmetic such as this isn’t that hard, but the kind of instructions that people want to give computers (like “print the following sentence”, or “repeat the following 100 times”) are much harder to build circuitry for.

**Jargon Buster**

The electronics in computers uses circuitry that mainly just works with two values (represented as high and low voltages) to make it reliable and fast. This system is called *binary*, and is often written on paper using zeroes and ones. There’s a lot more about binary in the [*Data representation*](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/DataRepresentation.html#data-representation) chapter, and it’s worth having a quick look at the first section of that now if you haven’t come across binary before.

So instead of building computers that can understand these high level instructions that you find in languages like Python (or Java, Basic, JavaScript, C and so on), we build computers that can follow a very limited set of instructions, and then we write programs that convert the instructions in the standard languages people write programs in into the simple instructions that the circuitry can directly carry out. The language of these simple instructions is a low level programming language often referred to as machine code.

The conversion from a high level to a low level language can involve *compiling*, which replaces the high level instructions with machine code instructions that can then be run, or it can be done by *interpreting*, where each instruction is converted and followed one by one, as the program is run. In reality, a lot of languages use a mixture of these, sometimes compiling a program to an intermediate language, then interpreting it (Java does this). The language we looked at earlier, Python, is an interpreted language. Other languages such as C++ are compiled. We will talk more about compiling and interpreting later.

We will start with looking at some other programming languages that programmers use to give instructions to computers, then we will look at low level languages and how computers actually carry out the instructions in them, and then finally we will talk about how we convert programs that were written by humans in a high level language into a low level language that the computer can carry out.

## 4.2\. MACHINE CODE (LOW LEVEL LANGUAGES)[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#machine-code-low-level-languages "Permalink to this headline")

A computer has to carry out instructions on physical circuits. These circuits contain transistors laid out in a special way that will give a correct output based on the inputs.

Data such as numbers (represented using binary) have to be put into storage places called registers while the circuit is processing them. Registers can be set to values, or data from memory can be put into registers. Once in registers, they can be added, subtracted, multiplied, divided, or be checked for equality, greater than, or less than. The output is put into a register, where it can either be retrieved or used in further arithmetic.

All computers have a machine code language (commonly referred to as an instruction set) that is used to tell the computer to put values into registers, to carry out arithmetic with the values in certain registers and put the result into another specified register like what we talked about above. Machine code also contains instructions for loading and saving values from memory (into or out of registers), jumping to a certain line in the program (that is either before or after the current line), or to jump to the line only if a certain condition is met (by doing a specified comparisons on values in registers). There are also instructions for handling simple input/ output, and interacting with other hardware on the computer.

The instructions are quite different to the ones you will have seen before in high level languages. For example, the following program is written in a machine language called MIPS; which is used on some embedded computer systems. We will use MIPS in examples throughout this chapter.

It starts by adding 2 numbers (that have been put in registers $t0 and $t1) and printing out the result. It then prints “Hello World!” Don’t worry, we aren’t about to make you learn how to actually program in this language! And if you don’t really understand the program, that’s also fine because many software engineers wouldn’t either! (We are showing it to you to help you to appreciate high level languages!)

~~~

.data

str: .asciiz "\nHello World!\n"

#You can change what is between the quotes if you like

.text

.globl main

main:

#Do the addition

#For this, we first need to put the values to add into registers ($t0 and $t1)

li $t0, 10 #You can change the 10

li $t1, 20 #You can change the 20

#Now we can add the values in $t0 and $t1, putting the result in special register $a0

add $a0, $t0, $t1

#Set up for printing the value in $a0\. A 1 in $v0 means we want to print an int

li $v0, 1

#The system call looks at what is in $v0 and $a0, and knows to print what is in $a0

syscall

#Now we want to print Hello World

#So we load the (address of the) string into $a0

la $a0, str

#And put a 4 in $v0 to mean print a string

li $v0, 4

#And just like before syscall looks at $v0 and $a0 and knows to print the string

syscall

#Nicely end the program

li $v0, 0

jr $ra

~~~

You can run this program using an online MIPS emulator. This needs to be done in 2 steps:

* [Copy paste the code into the black box on the page from this link](http://alanhogan.com/asu/assembler.php) (remove ALL existing text in the box), and then click the Assemble button.

* [Copy paste the output in the “Assembler Output” box into the box on the page from this link](http://alanhogan.com/asu/simulator.php) (remove ALL existing text in the box), and click the Simulate Execution button, and the output should appear in a box near the top of the page

Once you have got the program working, try changing the values that are added. The comments tell you where these numbers that can be changed are. You should also be able to change the string (text) that is printed without too much trouble also. As a challenge, can you make it so that it subtracts rather than adds the numbers? Clue: instruction names are always very short. Unfortunately you won’t be able to make it multiply or divide using this emulator as this seems to not currently be supported. Remember that to rerun the program after changing it, you will have to follow both steps 1 and 2 again.

You may be wondering why you have to carry out both these steps. Because computers work in 1’s and 0’s, the instructions need to simply be converted into hexadecimal. Hexadecimal is a shorthand notation for binary numbers. *Don’t muddle this process with compiling or interpreting!* Unlike these, it is much simpler as in general each instruction from the source code ends up being one line in the hexadecimal.

One thing you might have noticed while reading over the possible instructions is that there is no loop instruction in MIPS. Using several instructions though, it actually is possible to write a loop using this simple language. Have another read of the paragraph that describes the various instructions in MIPS. Do you have any ideas on how to solve this problem? It requires being quite creative!

The jumping to a line, and jumping to a line if a condition is met can be used to make loops! A very simple program we could write that requires a loop is one that counts down from five and then says “Go!!!!” once it gets down to one. In Python we can easily write this program in three lines.

~~~

for i in range(5,0,-1): #Start at 5, count down by 1 each time, when we get to 0 stop

print(i)

print("GO!!!!!")

~~~

But in MIPS, it isn’t that straight forward. We need to put values into registers, and we need to build the loop out of jump statements. Firstly, how can we design the loop?

And the full MIPS program for this is as follows. You can go away and change it.

~~~

#Define the data strings

.data

go_str: .asciiz "GO!!!!!\n"

new_line: .asciiz "\n"

.text

#Where should we start?

.globl main

main:

li $t0, 5 #Put our starting value 5 into register $t0\. We will update it as we go

li $t1, 0 #Put our stopping value 0 into register $t1

start_loop: #This label is just used for the jumps to refer to

#This says that if the values in $t0 and $t1 are the same, it should jump down to the end_loop label.

#This is the main loop condition.

beq $t0, $t1, end_loop

#These three lines prepare for and print the current int

move $a0, $t0 # It must be moved into $a0 for the printing

li $v0, 1

syscall

#These three lines print a new line character so that each number is on a new line

li $v0, 4

la $a0, new_line

syscall

addi $t0, $t0, -1 #Add -1 to the value in $t0, i.e decrement it by 1

j start_loop #Jump back up to the start_loop label

end_loop: #This is the end loop label that we jumped to when the loop is false

#These three lines print the “GO!!!!” string

li $v0, 4

la $a0, go_str

syscall

#And these 2 lines make the program exit nicely

li $v0, 0

jr $ra

~~~

Can you change the Python program so that it counts down from 10? What about so it stops at 5? (You might have to try a couple of times, as it is somewhat counter intuitive. Remember that when i is the stopping number, it stops there and does not run the loop for that value!). And what about decrementing by 2 instead of 1? And changing the string (text) that is printed at the end?

You probably found the Python program not too difficult to modify. See if you can make these same changes to the MIPS program.

If that was too easy for you, can you make both programs print out “GO!!!!” twice instead of once? (you don’t have to use a loop for that). And if THAT was too easy, what about making each program print out “GO!!!!” 10 times? Because repeating a line in a program 10 times without a loop would be terrible programming practice, you’d need to use a loop for this task.

More than likely, you’re rather confused at this point and unable to modify the MIPS program with all these suggested changes. And if you do have an additional loop in your MIPS program correctly printing “GO!!!” 10 times, then you are well on your way to being a good programmer!

So, what was the point of all this? These low level instructions may seem tedious and a bit silly, but the computer is able to directly run them on hardware due to their simplicity. A programmer can write a program in this language if they know the language, and the computer would be able to run it directly without doing any further processing. As you have probably realised though, it is extremely time consuming to have to program in this way. Moving stuff in and out of registers, implementing loops using jump and branch statements, and printing strings and integers using a three line pattern that you’d probably never have guessed was for printing had we not told you leaves even more opportunities for bugs in the program. Not to mention, the resulting programs are extremely difficult to read and understand.

Because computers cannot directly run the instructions in the languages that programmers like, high level programming languages by themselves are not enough. The solution to this problem of different needs is to use a compiler or interpreter that is able to convert a program in the high level programming language that the programmer used into the machine code that the computer is able to understand.

These days, few programmers program directly in these languages. In the early days of computers, programs written directly in machine language tended to be faster than those compiled from high level languages. This was because compilers weren’t very good at minimising the number of machine language instructions, referred to as *optimizing*, and people trained to write in machine code were better at it. These days however, compilers have been made a lot smarter, and can optimize code far better than most people can. Writing a program directly in machine code may result in a program that is *less* optimized than one that was compiled from a high level language. Don’t put in your report that low level languages are faster!

This isn’t the full story; the MIPS machine code described here is something called a Reduced Instruction Set Architecture (RISC). Many computers these days use a Complex Instruction Set Architecture (CISC). This means that the computer chips can be a little more clever and can do more in a single step. This is well beyond the scope of this book though, and understanding the kinds of things RISC machine code can do, and the differences between MIPS and high level languages is fine at this level, and fine for most computer scientists and software engineers.

In summary, we require low level programming languages because the computer can understand them, and we require high level programming languages because humans can understand them. A later section talks more about compilers and interpreters; programs that are used to convert a program that is written in a high level language (for humans) into a low level language (for computers).

## 4.3\. A BABEL OF PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#a-babel-of-programming-languages "Permalink to this headline")

There are many different programming languages. Here we have included a small subset of languages, to illustrate the range of purposes that languages are used for. There are many, many more languages that are used for various purposes, and have a strong following of people who find them particularly useful for their applications.

For a much larger list you can [check Wikipedia here](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_programming_languages).

### 4.3.1\. PYTHON[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#python "Permalink to this headline")

Python is a widely used language, that has also become very popular as a teaching language. Many people learn Python as their first programming language. In the introduction, we looked at some examples of Python programs, for those who have never programmed before.

Originally though, Python was intended to be a scripting language. Scripting languages have syntax that makes them quick to write programs for file processing in, and for doing repetitive tasks on a computer.

As an example of a situation where Python is very useful, imagine your teacher has given 5 quizzes throughout the year, and recorded the results for each student in a file such as this (It could include more than 6 students), where each student’s name is followed by their scores. Some students didn’t bother going to class for all the quizzes, so have less than 5 results recorded.

~~~

Karen 12 12 14 18 17

James 9 7 1

Ben 19 17 19 13

Lisa 9 1 3 0

Amalia 20 20 19 15 18

Cameron 19 15 12 9 3

~~~

She realises she needs to know the average (assuming 5 quizzes) that each student scored, and with many other things to do does not want to spend much time on this task. Using python, she can very quickly generate the data she needs in less than 10 lines of code.

Note that understanding the details of this code is irrelevant to this chapter, particularly if you aren’t yet a programmer. Just read the comments (the things that start with a “#”) if you don’t understand, so that you can get a vague idea of how the problem was approached.

~~~

raw_scores_file = open("scores.txt", "r") #Open the raw score file for reading

processed_scores_file = open("processed_scores.txt", "w") #Create and open a file for writing the processed scores into

for line in raw_scores_file.readlines(): #For each line in the file

name = line.split()[0] #Get the name, which is in the first part of the line

scores_on_line = [int(score) for score in line.split()[1:]] #Get a list of the scores, which are on the remainder of the line after the name

average = sum(scores_on_line)/5 #Calculate the average, which is the sum of the scores divided by 5

processed_scores_file.write(name + " " + str(average) + "\n") #Write the average to the processed scores output file

raw_scores_file.close() #Close the raw scores file

processed_scores_file.close() #Close the processed scores file

~~~

This will generate a file that contains each student’s name followed by the result of adding their scores and dividing the sum by 5\. You can try the code if you have python installed on your computer (it won’t work on the online interpreter, because it needs access to a file system). Just put the raw data into a file called “scores.txt” in the same format it was displayed above. As long as it is in the same directory as the source code file you make for the code, it will work.

This problem could of course be solved in any language, but some languages make it far simpler than others. Standard software engineering languages such as Java, which we talk about shortly, do not offer such straight forward file processing. Java requires the programmer to specify what to do if opening the file fails in order to prevent the program from crashing. Python does not require the programmer to do this, although does have the option to handle file opening failing should the programmer wish to. Both these approaches have advantages in different situations. For the teacher writing a quick script to process the quiz results, it does not matter if the program crashes so it is ideal to not waste time writing code to deal with it. For a large software system that many people use, crashes are inconvenient and a security risk. Forcing all programmers working on that system to handle this potential crash correctly could prevent a lot of trouble later on, which is where Java’s approach helps.

In addition to straight forward file handling, Python did not require the code to be put inside a class or function, and it provided some very useful built in functions for solving the problem. For example, the function that found the sum of the list, and the line of code that was able to convert the raw line of text into a list of numbers (using a very commonly used pattern).

This same program written in Java would require at least twice as many lines of code.

There are many other scripting languages in addition to Python, such as Perl, Bash, and Ruby.

### 4.3.2\. SCRATCH[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#scratch "Permalink to this headline")

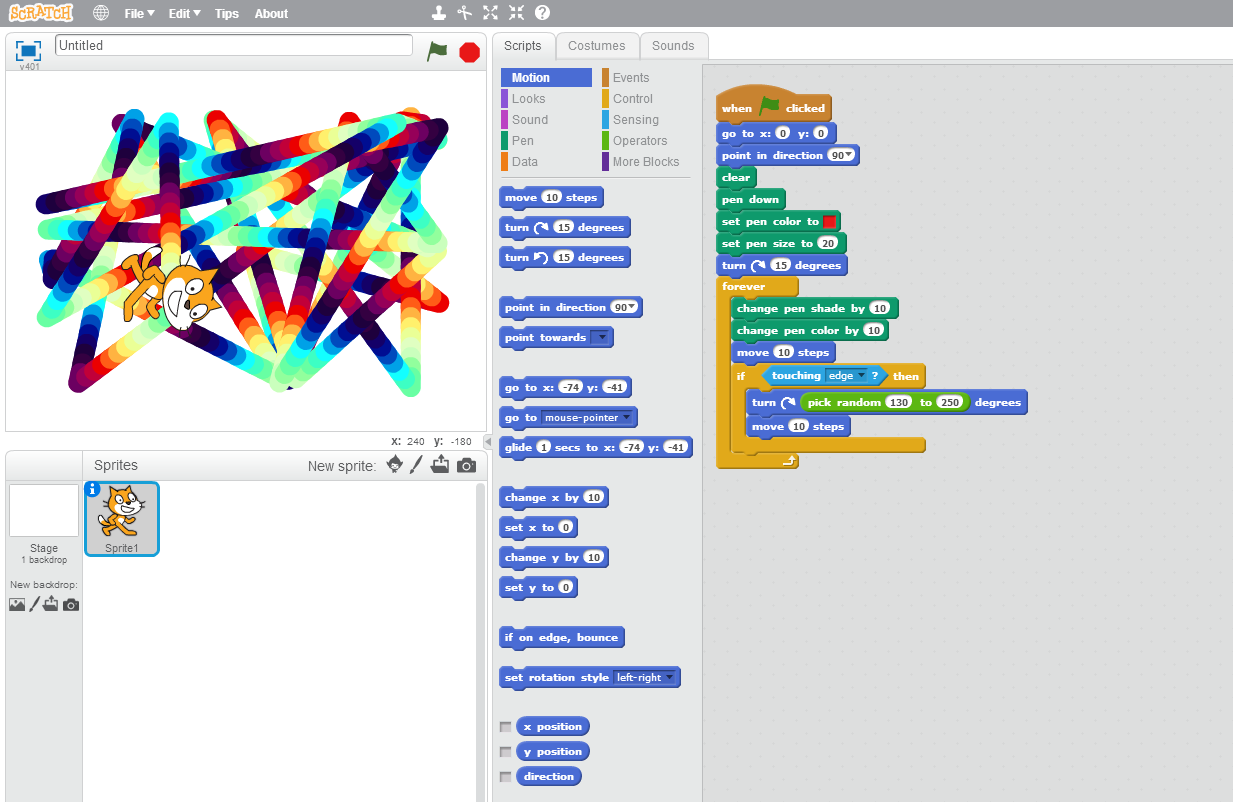

Scratch is a programming language used to teach people how to program. A drag and drop interface is used so that new programmers don’t have to worry so much about syntax, and programs written in Scratch are centered around controlling cartoon characters or other sprites on the screen.

Scratch is never used in programming in industry, only in teaching. If you are interested in trying Scratch, [you can try it out online here](http://scratch.mit.edu/projects/editor/?tip_bar=getStarted), no need to download or install anything.

[](http://scratch.mit.edu/projects/19711355/#editor)

Click the image above to load the project and try it for yourself.

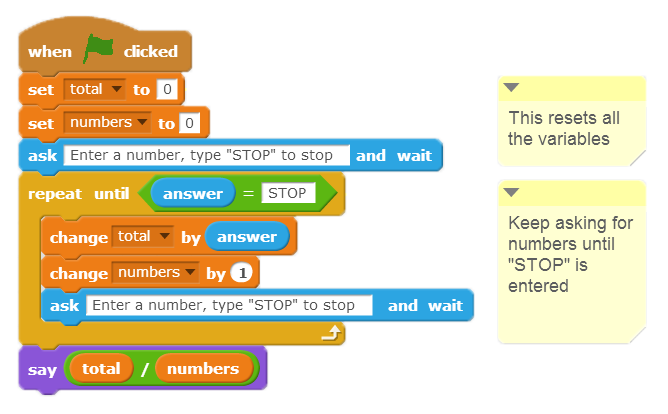

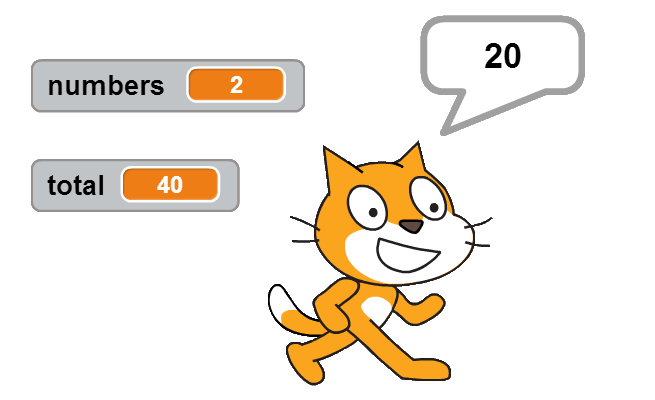

This is an example of a simple program in Scratch that is similar to the programs we have above for Python and Java. It asks the user for numbers until they say “stop” and then finds the average of the numbers given.

And this is the output that will be displayed when the green flag is clicked:

Scratch can be used for simple calculations, creating games and animations. However it doesn’t have all the capabilities of other languages.

Other educational languages include Alice and Logo. Alice also uses drag and drop, but in a 3D environment. Logo is a very old general purpose language based on Lisp. It is not used much anymore, but it was famous for having a turtle with a pen that could draw on the screen, much like Scratch. The design of Scratch was partially influenced by Logo. These languages are not used beyond educational purposes, as they are slow and inefficient.

### 4.3.3\. JAVA[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#java "Permalink to this headline")

Java is a popular general purpose software engineering language. It is used to build large software systems involving possibly hundreds or even thousands of software engineers. Unlike Python, it forces programmers to say how certain errors should be handled, and it forces them to state what type of data their variables are intended to hold, e.g. *int* (i.e. a number with no decimal places), or *String* (some text data). Python does not require types to be stated like this. All these features help to reduce the number of bugs in the code. Additionally, they can make it easier for other programmers to read the code, as they can easily see what type each variable is intended to hold (figuring this out in a python program written by somebody else can be challenging at times, making it very difficult to modify their code without breaking it!)

This is the Java code for solving the same problem that we looked at in Python; generating a file of averages.

~~~

import java.io.*;

import java.util.*;

public class Averager

{

public static void main() {

try {

Scanner scanner = new Scanner(new File("scores.txt"));

PrintStream outputFile = new PrintStream(new File("processed_scores.txt"));

while (scanner.hasNextLine()) {

String name = scanner.next();

Scanner numbersToRead = new Scanner(scanner.nextLine());

int totalForLine = 0;

while (numbersToRead.hasNextInt()) {

totalForLine += numbersToRead.nextInt();

}

outputFile.println(name + " " + totalForLine/5.0 + "\n");

}

outputFile.close();

}

catch (IOException e) {

System.out.println("The file could not be opened!" + e);

}

print("I am finished!");

}

}

~~~

While the code is longer, it ensures that the program doesn’t crash if something goes wrong. It says to *try* opening and reading the file, and if an error occurs, then it should *catch* that error and print out an error message to tell the user. The alternative (such as in Python) would be to just crash the program, preventing anything else from being able to run it. Regardless of whether or not an error occurs, the “I am finished!” line will be printed, because the error was safely “caught”. Python is able to do error handling like this, but it is up to the programmer to do it. Java will not even compile the code if this wasn’t done! This prevents programmers from forgetting or just being lazy.

There are many other general software engineering languages, such as C# and C++. Python is sometimes used for making large software systems, although is generally not considered an ideal language for this role.

### 4.3.4\. JAVASCRIPT[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#javascript "Permalink to this headline")

* Interpreted in a web browser

* Similar language: Actionscript (Flash)

Note that this section will be completed in a future version of the field guide. For now, you should refer to wikipedia page for more information.

### 4.3.5\. C[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#c "Permalink to this headline")

* Low level language with the syntax of a high level language

* Used commonly for programming operating systems, and embedded systems

* Programs written in C tend to be very fast (because it is designed in a way that makes it easy to compile it optimally into machine code)

* Bug prone due to the low level details. Best not used in situations where it is unnecessary

* Related languages: C++ (somewhat)

Note that this section will be completed in a future version of the field guide. For now, you should refer to wikipedia page for more information.

### 4.3.6\. MATLAB[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#matlab "Permalink to this headline")

* Used for writing programs that involve advanced math (calculus, linear algebra, etc.)

* Not freely available

* Related languages: Mathematica, Maple

Note that this section will be completed in a future version of the field guide. For now, you should refer to wikipedia page for more information.

### 4.3.7\. ESOTERIC PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#esoteric-programming-languages "Permalink to this headline")

Anybody can make their own programming language. Doing so involves coming up with a syntax for your language, and writing a parser and compiler or interpreter so that programs in your language can be run. Most programming languages that people have made never become widely used.

In addition to programming languages that have practical uses, people have made many programming languages that were intended to be nothing more than jokes, or to test the limits of how obscure a programming language can be. Some of them make the low level machine languages you saw earlier seem rather logical! Wikipedia has a list of such languages. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Esoteric_programming_language](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Esoteric_programming_language)

You could even make your own programming language if you wanted to!

## 4.4\. HOW DOES THE COMPUTER PROCESS YOUR PROGRAM?[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#how-does-the-computer-process-your-program "Permalink to this headline")

A programming language such as Python or Java is implemented using a program itself — the thing that takes your Python program and runs it is a program that someone has written!

Since the computer hardware can only run programs in a low level language (machine code), the programming system has to make it possible for your Python instructions to be executed using only machine language. There are two broad ways to do this: interpreting and compiling.

[This 1983 video](http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_C5AHaS1mOA) provides a good analogy of the difference between an interpreter and a compiler.

The main difference is that a compiler is a program that converts your program to machine language, which is then run on the computer. An interpreter is a program that reads your program line by line, works out what those instructions are, and does them immediately.

There are advantages to both approaches, and each one suits some languages better than others. In reality, most modern languages use a mixture of compiling and interpreting. For example, most Java programs are *compiled* to an “intermediate language” called ByteCode, which is closer to machine code than Java. The ByteCode is then executed by an interpreter.

If your program is to be distributed for widespread use, you will usually want it to be in machine code because it will run faster, the user doesn’t have to have an interpreter for your particular language installed, and when someone downloads the machine code, they aren’t getting a copy of your original high-level program. Languages where this happens include C#, Objective C (used for programming iOS devices), Java, and C.

Interpreted programs have the advantage that they can be easier to program because you can test them quickly, trace what is happening in them more easily, and even sometimes type in single instructions to see what they do, without having to go through the whole compilation process. For this reason they are widely used for introductory languages (for example, Scratch and Alice are interpreted), and also for simple programs such as scripts that perform simple tasks, as they can be written and tested quickly (for example, languages like PHP, Ruby and Python are used in these situations).

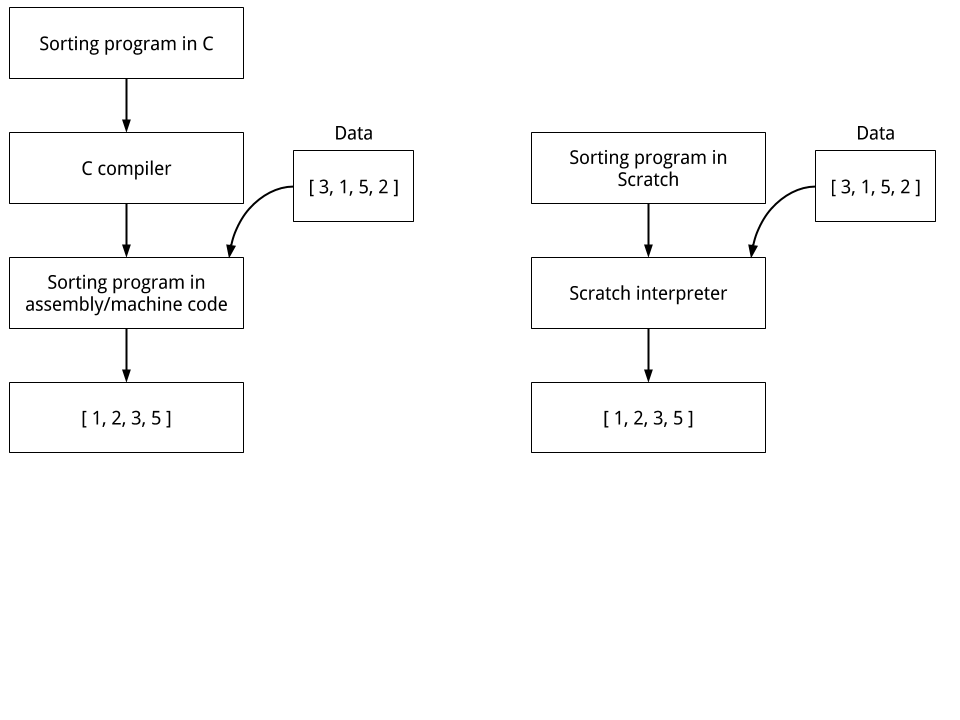

The diagram below shows the difference between what happens in an interpreter and compiler if you write and run a program that sorts some numbers. The compiler produces a machine code program that will do the sorting, and the data is fed into that second program to get the sorted result. The interpreter simply does the sorting on the input by immediately following the instructions in the program. The compiler produces a machine code program that you can distribute, but it involves an extra phase in the process.

## 4.5\. THE WHOLE STORY!

There are many different programming languages, and new ones are always being invented. Each new language will need a new compiler and/or interpreter to be developed to support it. Fortunately there are good tools to help do this quickly, and some of these ideas will come up in the *Formal Languages* chapter, where things like regular expressions and grammars can be used to describe a language, and a compiler can be built automatically from the description.

The languages we have discussed in this chapter are ones that you are likely to come across in introductory programming, but there are some completely different styles of languages that have very important applications. There is an approach to programming called [Functional programming](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Functional_programming) where all operations are formulated as mathematical functions. Common languages that use functional techniques include Lisp, Scheme, Haskel, Clojure and F#; even some conventional languages (such as Python) include ideas from functional programming. A pure functional programming style eliminates a problem called *side effects*, and without this problem it can be easier to make sure a program does exactly what it is intended to do. Another important type of programming is [logic programming](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Logic_programming), where a program can be thought of as a set of rules stating what it should do, rather than instructions on how to do it. The most well-known logic programming language is Prolog.

## 4.6\. FURTHER READING[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#further-reading "Permalink to this headline")

### 4.6.1\. USEFUL LINKS[](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#useful-links "Permalink to this headline")

* The [TeachICT lesson on programming languages](http://www.teach-ict.com/gcse_computing/ocr/216_programming/programming_languages/miniweb/index.htm) covers many of the topics in this chapter

* CS Online has a [quick overview of this topic](http://courses.cs.vt.edu/~csonline/ProgrammingLanguages/Lessons/Introduction/index.html)

* Wikipedia entries on [Programming language](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Programming_language), [High level language](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High-level_programming_language), and [`](http://csfieldguide.org.nz/ProgrammingLanguages.html#id2)Low level language ’_

* [website including posters comparing programming languages](http://programming.dojo.net.nz/) by Samuel Williams

* [tutorial comparing programming languages](http://holowczak.com/programming-concepts-tutorial-programmers/)

* a [discussion of interpreters and compilers](http://pathfinder.scar.utoronto.ca/~dyer/csca57/book_P/node7.html)

* a [poster with full details of the file content in an executable file](http://code.google.com/p/corkami/wiki/PE101?show=content) (the exe format)

* David Bolton explains a [Programming Language](http://cplus.about.com/od/introductiontoprogramming/p/programming.htm), [Compiler](http://cplus.about.com/od/introductiontoprogramming/p/compiler.htm), and [the difference between Compilers and Interpreters](http://cplus.about.com/od/introductiontoprogramming/a/compinterp.htm).

* [Computerworld article on the A to Z of programming languages](http://www.computerworld.com.au/article/344826/z_programming_languages/)

* [What is Python?](http://python.about.com/od/gettingstarted/ss/whatispython_4.htm) (compared with other languages)

* A [very large poster showing a timeline of the development of programming languages](http://www.levenez.com/lang/)

* [Hello World program in hundreds of programming languages](http://www.roesler-ac.de/wolfram/hello.htm)

* [99 bottles of beer song in hundreds of programming languages](http://99-bottles-of-beer.net/)